Magazine: The Song Heard 'Round the World

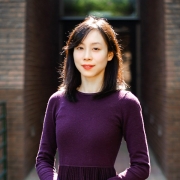

Carol Muller wants to teach you—wherever you are, and however she can. Anchored in the Music Building, where she conducts her perennially popular “World Music and Culture” and other classes, the professor has stretched beyond Penn’s campus by sending students to research the use of music in West Philadelphia, through a summer class that is half online and half on the ground in South Africa, and with internet-based courses for undergraduate and LPS students.

Now her audience has increased by an order of magnitude: This summer she led an online class for 36,000 people, two-thirds of whom lived outside the United States. Her students ranged in age from their late teens into their 90s and in location from New Jersey to Kazakhstan. Appropriately, the topic was “Listening to World Music.”

The class was conducted through Coursera, a research-based online teaching initiative developed by professors at Stanford. Thirty-three universities, including Penn, Princeton and Duke, are partnering with the initiative to increase access to elite education for people around the world. When Muller heard about the opportunity, she says, “My gut reaction was, that’s it. This is something I want to do.” A native of South Africa, she understands the need for quality instruction in many parts of the world. The chance to make a piece of a Penn education available to more people, for their own enrichment and that of their communities, she says, “is like the perfect vehicle for me.”

Muller seems just as ideal for Coursera. Her ethnomusicology career is rooted in her background growing up in apartheid South Africa, where even music was affected: radio stations were segregated, language differences divided people and musicians were censored and harassed if they stepped over the line. Her father was a minister who strongly believed in the power of music to draw people together. When she was in her teens, he moved into a ministry of reconciliation, going into the townships, setting up churches and communities and illegally ordaining the first black elder in his white church. Muller says, “He was a very gentle soul, but he just believed that you love God and love your neighbor, and your neighbor could be in a township, right?”

As a student at the University of Natal (now KwaZulu-Natal), Muller learned to gumboot dance by illegally going with a colleague into the townships in Durban. Gumboot dancing, which she likens to tap dancing with heavy boots on, began in South African gold mines. Forbidden to speak to each other, miners slapped their Wellington-style gumboots to send messages. It evolved into a working class art form known to every black South African, but Muller had no idea it existed before a professor introduced her.

“It was a completely life-transforming experience,” she says. “There were States of Emergency declared while we were in the townships. One time I really think my mother thought she might never see me again.” But they developed good relationships with the dancers, who would call to warn them when it wasn’t safe to come.

She says, “For me, music has been the door through which you begin to communicate across difference. I think having lived under apartheid and realizing what cultural separation does to people, maybe that is the thing that really pushes me to find a way, a common space, a common ground.”

Because of her interest in reaching out through teaching, the School just awarded Muller the new title of Fellow in Digital and Community Engagement. Digitally speaking, she’s come a long way since 2003. She had just gotten tenure at Penn when the School of Arts and Sciences launched online teaching and asked her if she would be a pioneer. “I’d never even used PowerPoint,” says Muller. She also had to digitize the audio and video clips she used, an average of 15 per class. She taught the class from a makeshift studio.

Nine years later, videos and CDs seem like artifacts and her online classes for undergraduates and students in the College of Liberal and Professional Studies are polished, popular, and as interactive as those in the classroom. They use the Arts and Sciences Learning Commons, a system which provides course materials, communication and learning tools for Penn’s online classes. Through the Commons, class time is a real-time meeting between Muller and her students. With a live chat, students text questions and comment on the material as she’s teaching, as well as about assignments, deadlines and concerts.

“It becomes a much more efficient way of conveying material,” says Muller. “I ask a question and everyone’s responding immediately. Students know what other students are thinking, I know what students are thinking, and while I’m teaching, the graduate student teaching fellows are answering those questions in the live text. You can do two things in the same moment.”

Whenever and however she teaches world music, she starts with the sound. “I require them to listen to music they may not even define as music—to their ears it doesn’t feel like music—and listen repeatedly, and at least it becomes familiar, not so alien,” she says. “They might not like it at the end, but they understand the internal logic, how it works musically, acoustically, socially and culturally and politically and religiously. Initially, it’s sound; it’s music when you understand how it works.”

Penn’s Academically Based Community Service (ABCS) classes have given Muller another opportunity to stretch her teaching beyond the campus. Over the last seven years, she and her students have run an expanding web site, West Philly Music, to archive research resulting from classes which focus on cultural music traditions in the neighborhoods around Penn. The students meet and work with residents to research gospel, jazz and Islamic performance. “They’re going out and generating actual material,” says Muller. “They’re in conversation with other histories and finding how to work together with people.” The class has evolved along with the Internet. This year students will go back to review and recontextualize research from past years, using a blog linked to the website. The material will eventually become chapters in a book about the history of gospel that Muller and the community want to produce.

Muller’s summer “Penn in Grahamstown” course also puts students in the field, this time in Africa. Beginning with four web sessions, the class then meets up live in Grahamstown, South Africa, during the National Arts Festival, experiencing a live festival in a digital age. The trip is challenging. “While it’s full of pleasure, they have to learn to pace themselves, manage on the run, keep their wits about them, take photographs, keep thinking,” says Muller. Students track all the input with individual blogs, contributing some entries to a public website. After the trip, they write a reflection paper to help them process the experience.

And now she’s added Coursera, which Muller calls “a thinking work in progress.” After nine years of online teaching experience, she found that a fully global audience posed new challenges: time zones, cultural and technological differences, and having to find new, publically accessible music samples. She and her students addressed and reconciled issues as they arose, and the enormously diverse class learned and interacted, not only from Muller but from each other.

“The cultural stuff—that’s what makes Coursera great for the humanities,” says Muller. “The insider perspectives, so that you really are learning different ways of doing things and hearing.” Students organized groups using Facebook and other social media, shared their own experiences with the music and linked to samples from their cultures. “I didn’t even know some of this music existed,” she says. “It was pretty exciting.”

No matter the forum, Muller’s teaching experiences all meld to inform her pedagogy. In Grahamstown, the festival made her class think anew about the power of art in life, inspiring her to ask her ABCS students this year to create a piece of art designed to raise questions. Her Coursera experience persuaded her to try peer grading with her smaller online courses. She’ll provide a rubric for discussion forums and students will grade each other’s contributions. “It means that students know what other students are thinking,” she says. “So I think that there is much to learn from that.”

Muller’s dedication to improving and expanding her teaching is taking her research and publishing in new directions, as well. She’ll follow her most recent book, an important publication on women and jazz in South Africa, with a textbook for Oxford University Press that will supplement the lectures and slides for her online world music course. The text will also offer research projects and other information that can be explored more by smaller user groups afterward.

Muller hopes all her courses—in any format—will open up students’ playlists. “That could just mean listening to hip hop in Turkish or Mandarin, to see how it translates in these places,” she says. She wants them to be aware of world music when they hear it, like “pygmy pop” used in commercials, and to ask about its background. “There are all these access points where they can experiment, explore, go a little beyond what they usually do, to learn.”

Ultimately, she says, “I want students to travel abroad at the end, and to say ‘I want to go to Senegal instead of Paris to learn French.’ My goal in teaching is not just to make students reproduce knowledge, but to make their knowledge matter in their lives. I want to push students to really think about things because life is so rich.”