Magazine: Visions of Grandeur

While the election is behind us, the campaign rhetoric lives on in public discourse. The two visions of America presented by the campaigns—one that combines individualism, faith in free markets, and a limited role of government versus an America built on commitment to social community, a strong role for government, and strong social safety nets—are the latest manifestations of a philosophical divide that has a long history in American politics and culture. Bringing in their expertise from political science, philosophy and ethics, three SAS faculty take a look back at the competing visions expressed through the Romney and Obama campaigns, answering such questions as: What can a historical analysis of each party’s origins teach us about their policy plans? How do we define what a “moral” government is? And how might other models illuminate issues within our own governing body?

Liberalism—What's in a Name?

The term “liberal” has become a lightning rod of sorts, worn like a badge of honor by those on the left, and used as a condemnation by those on the right. Its derivation might not only surprise you, but also act as a crucial guide to understanding the visions each candidate’s campaign came to represent. “The Republican Party’s economic position evolved from what’s called ‘classical liberalism’—fathered by figures like Scottish philosopher Adam Smith, and classical economists like David Ricardo and Thomas Robert Malthus,” says Samuel Freeman, Avalon Professor in the Humanities and Professor of Philosophy and Law. “Laissez-faire capitalism—now endorsed by big-business Republicanism—grew out of this same movement.” On the other hand, today’s Democrats, Freeman says, “represent what’s often referred to as ‘new liberalism,’ which emphasizes the welfare state, and is thus defined by programs like Social Security and Medicare.”

The evolution of liberal public assistance has roots in The Poor Laws, says Freeman, which were first enacted in 1601 in Elizabethan England to ensure the poor wouldn’t starve to death and that shelter would be provided for orphans and other helpless people. The Republican Party, historically, accepted this as the government’s responsibility, though they often argued it was the duty of individual states. “It’s not that the Romney camp was opposed to health-care coverage, because he himself instituted it in Massachusetts,” says Freeman. “They just believed that it was a duty for states and not for the Federal Government.” Democrats, he says, have become the party of social insurance, distinguishable from public assistance—what was called poor relief in England. This includes benefits like disability insurance, unemployment insurance and health care. “The idea of social insurance is that everyone earning an income pays into it and the government itself pays back when people need the care—a philosophy supported by the Obama campaign.”

When Romney nominated Paul Ryan as his running mate, a new political philosophy was introduced into the race. “Ryan and his budget are distinctive from both classical and new liberalism,” says Freeman. “Ryan is what we call a libertarian. Libertarians don’t believe government should have a role providing for the poor or anyone else. They believe private charity should replace public welfare, particularly when the country faces such a large federal deficit.”

It’s not all apples and oranges, though, Freeman says. The face of liberalism is still changing. “Obama has always been economically conservative—he’s basically a classical liberal himself in many respects. When he came into office, he chose some people from George W. Bush’s economic team and continued many of the same policies. So we’re definitely at an interesting crossroads—the ‘new liberal’ Democrats are moving to the right, and the ‘classically liberal’ Republicans are verging on extreme right libertarianism.”

Samuel Freeman is the Avalon Professor in the Humanities and a professor of philosophy and law.

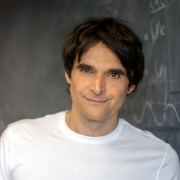

The Numbers Game

The University of Pennsylvania’s founder Benjamin Franklin may have hit the nail on the head with his claim about death and taxes, and though taxes may be an inevitability, that doesn’t mean tax policy should be immovable. It’s an issue that has plagued both political parties for decades, greatly impacting the campaigns both Obama and Romney ran. “The issue is we’ve had 50-plus years now of having it both ways,” says John DiIulio, Frederic Fox Leadership Professor of Politics, Religion, and Civil Society and Professor of Political Science, who likes to think himself as the “plumber” counterpart to political philosophers. “If you increase spending and cut taxes at the same time, you’re going to create deficits and a debt problem that will have to be faced. We can’t continue to be operationally liberal while being philosophically conservative.” The solution to this stark reality, DiIulio says, is that taxes across the board must be reevaluated if we expect to enjoy the same social insurance commodities. “Republicans refuse to raise taxes on the rich, while Democrats view tax increases on the middle class as political kryptonite.”

The other option is to drastically cut spending, which has been met with frustration and filibusters in congress. The Paul Ryan budget, for instance, viewed as one of the most aggressive answers to fiscal debt, offers social welfare cuts as a potential solution. But the controversial cuts, DiIulio says, would barely put a dent in the deficit—and would come at a great cost. “When the economy falters, as it did for my own grandmother during the Great Depression, and the church and the community don’t have the resources to help, one of the only places to turn is to the largest political community: ‘Mr. Roosevelt,’ as my grandmother used to say, or in other words, the national government.” But it’s not just a moral or philosophical question, the plumber in DiIulio says. If you add up all the cuts to social welfare in the Ryan budget, it only amounts to three or four percent from total government (federal, state, and local) spending, over the next decade.

So what’s the solution? DiIulio says when bipartisanship fails politicians must turn to non-partisan commissions like Bowles-Simpson, whose debt reduction plans cut discretionary spending and reform the tax code. “Relatively less government spending in return for relatively more government administration of government programs should not be off the table. It’s often demonized, but in many instances, government works.”

John DiIulio is the Frederic Fox Leadership Professor of Politics, Religion, and Civil Society and a professor of political science.

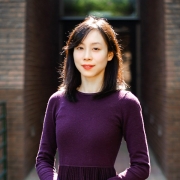

Credits vs. Guarantees; Respect vs. Harm

Do morality and politics go hand-in-hand? Amidst lofty—often conflicting—rhetoric from both campaigns, how does one tell right from wrong? What it means to be a moral society is at the heart of Kok-Chor Tan’s research. Tan, Associate Professor of Philosophy and author of Justice, Institutions, and Luck: The Site, Ground, and Scope of Equality, examines society through the lens of egalitarianism. Of utmost importance, he says, is a candidate’s vision for caring for the unfortunate, an issue that sharply divided the Obama and Romney platforms.

“Egalitarianism believes that providing for those who can’t provide for themselves due to misfortune is a matter of justice, and that people who are to be beneficiaries have a rightful claim to these things,” says Tan. “When these beneficiaries are made to depend upon private charity, they can be grateful when they get it, but have no cause for complaint if they don’t. A lack of institutional guarantee is an important difference. You don’t have to say, look, when I’m getting a wage next month, it’s going to be based on the goodwill of my boss.”

The Ryan budget, which fails to provide institutional guarantees, is at odds with the egalitarian model. Tan cites the budget’s Medicare reform plans as an important example. “If Medicare were to transition to a voucher system, expectations of care would be left to the vagaries of the marketplace. The voucher is a credit against future expense, while coverage under Medicare is a guarantee.” Egalitarianism must also be applied to tax reform, he says. Because redistribution is inevitably required if resources to support the disenfranchised are too scarce, money must float downward. Obama’s extension of the tax cuts passed during George W. Bush’s presidency is a failed opportunity under this model.

In regards to social justice, Tan cites two different rubrics. Egalitarians advocate a doctrine of respect as a way of understanding what kind of government restriction and intervention might be acceptable. “Restricting gay marriage does not accord equal respect,” says Tan. “A ban on an arrangement between two mutually consenting adults is a violation of this principle.” Another social justice guideline Tan cites is philosopher John Stuart Mill’s “harm principle.” Mill believed that people should be free to pursue whatever course they desire, as long as it doesn’t harm other persons. “Social policies and laws reflecting a certain view of social morality risk exceeding the limit set by the harm principle.” Ryan’s claim that he would repeal Obama’s mandate requiring insurance providers to cover birth control is an example.

One potential flaw in any egalitarian society is the possibility that a subset of the public might abuse support offered by the institution, a theory that the Romney camp cited, most infamously in a secretly recorded video featuring Romney remarking that 47 percent of the population are “victims” that depend on government support. The egalitarian philosophy believes that this group is relatively small, and that very few self-respecting individuals would abuse aid. Free speech can be seen as an analogy, Tan says. Some will abuse that right in order to participate in hate speech, but most members of society realize these anomalous individuals are part of the cost of the expectation of an authentic majority. “In the end, the egalitarian model requires a certain moral vision,” says Tan. “If we don’t care for those who are facing misfortune, we are alienating ourselves from one another.”

Kok-Chor Tan is an associate professor of philosophy.