Our Debt of Honor: A Q&A With Beth Linker on New Film That Traces the History of Disabled American Veterans

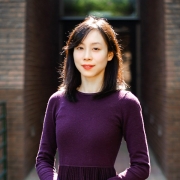

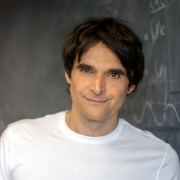

The United States celebrates Veteran’s Day each November, recognizing all those who have served in its armed forces. On November 10, 2015, PBS aired a new Ric Burns documentary, Debt of Honor: Disabled Veterans in American History, featuring Beth Linker, associate professor of history and sociology of science in Penn Arts and Sciences. Linker’s research focuses on the social and cultural history of U.S. medicine in the 19th and 20th centuries. She is the author of War’s Waste: Rehabilitation in World War I America. We talked to her about the film.

SUSAN AHLBORN: Tell me about Debt of Honor.

BETH LINKER: The film traces the history of disabled American veterans from the Revolutionary War to today, with a balance of disabled veterans and scholars. It opens with Representative Tammy Duckworth talking about the day she was injured, and includes Max Cleland, a Vietnam vet who lost three limbs and who was the director of the Veterans Administration [VA] under Jimmy Carter.

This kind of education about disabled veterans is really important today because we rely on less than 1 percent of the population to fight wars. Since the end of the draft after Vietnam, the “citizen soldier” is a relic of the past. Now that the U.S. relies on a professional standing Army, there is an inevitable estrangement between civil society and the military veterans. The greatest danger with this kind of distancing is that the nation enters ever more wars without an informed and engaged public providing a necessary check on the situation. Wars and their aftermath should be a part of our everyday political conservations—not just in the halls of Congress but also around the dinner table.

SA: Do you think it’s enough a part of the discussion around the upcoming presidential election?

BL: No, I don’t think so. In September I had a piece in the Boston Globe about the VA, which has been embroiled in scandals from the beginning of its history. After the Civil War there was a very robust pension system that cut checks to disabled veterans with no expectation that they do anything more. But around World War I, everyone looked at the war veteran as a problem, as an economic problem and a kind of aesthetic problem. So, like a lot of other progressive-era programs, the goal was to solve this problem with enough medicine and social engineering. The hope was to medically rehabilitate all these soldiers so that they wouldn’t have to receive any pensions and so the public wouldn’t see the human cost of war. From the beginning the VA was an experiment in cost-cutting measures.

SA: What else do disabled veterans have to deal with?

BL: I say in the film that these men went off to war—in World War I it was all men—and then they had to wage a second war when they came home, and it’s a war against their bodies, to make them whole again, to become able-bodied again, whether mentally or physically. That hasn’t changed.

SA: How do you think society views disabled veterans now?

BL: I think civilians were far more aware in the past of disabled soldiers because it was more likely you knew somebody in your family who would be in the military.

SA: Are we seeing a bigger ratio of disabled soldiers to war dead because of improvements in medical care?

BL: It’s a whole host of things, mostly the triage and nursing care, the whole team caring for these veterans. It’s better healthcare, especially on the front lines, so the survival rate goes up. And then of course things like blood transfusions and antibiotics improved survival rates.

So, yes, there potentially are more severely disabled veterans surviving their injuries. That said, one thing the film shows to be a constant over time is that the war wounded outnumber the war dead. This is not a new problem.

SA: How have things changed regarding mental health? Are we getting any better at recognizing and treating it?

BL: Some argue it’s hard to come out of a war unscathed even if you’re physically intact. Given what war makes a person do, transitioning back into civil society can be very challenging and difficult. Since I’m not a psychologist and I’m not researching that aspect, it’s hard for me to say if we’re getting better at it or not. I think there has always been an incredible stigma attached to it.

There is a kind of hierarchy of disabilities. My research is focused more on amputees and how they serve as a gold standard of the rehabilitation ideal because symbolically it can be very seductive to see an amputee without a limb and then with a limb on. And this becomes a signifier of the rehabilitation process and of progress and of how rehabilitation itself can make it so that there is no human cost to war. I think all other kinds of the rehabilitation ethos try to follow that model, but of course mental health is far more complicated than an amputation. And the other thing that we’re seeing more of with the current wars are brain injuries, and those are incredibly complicated.

SA: What would you recommend?

BL: Oh, I’m a historian, not a policy maker. But as a historian I would say there should be more education, from elementary school to high school to college—more coursework offered in the history of war and the aftermath of war. And it should include the many people who care for these veterans and consider what kind of resources are available to family and kin. It behooves us to do anything we can do to understand current-day policy. One way of doing that is to understand the history of how we got here.

We need care on many levels when it comes to disabled veterans. We need the 99 percent of today’s civilians to care about what happens before, during, and after a war. We need a politically informed and educated electorate. I feel like it’s our civic duty. If we’re not going to serve in the military, we at least need to be aware of what’s going on.