Penn Arts & Sciences Magazine: Hamlet's Ghost

To be, or not to be, I there’s the point,

To Die, to sleepe, is that all?

If this most famous of English passages sounds a little deficient to you, you’re not alone. Scholars and laypeople alike joined in the debate after 1823, when Sir Henry Bunbury found an old, poorly bound book in the house he’d inherited. It included a quarto (a small and flimsy copy) of Hamlet that had been published in 1603, a year earlier than any version previously known. And this Hamlet was different in some major ways from the play that had become venerated in the intervening two centuries.

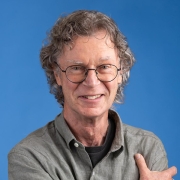

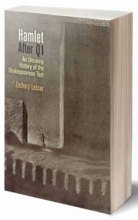

Associate Professor of English Zachary Lesser has just published “Hamlet” After Q1: An Uncanny History of the Shakespearean Text. He outlines some of the biggest differences: Q1 was about half the length, and many believed the poetry was not as good. The plot is basically the same, but the text is more religious, and Gertrude proclaims her innocence and plots against Claudius.

Everyone was talking about it. “The newspapers and popular magazines were filled with discussions of this,” says Lesser. “It’s as if not only the New Yorker but the National Enquirer were writing about it. People were fascinated.”

Just one added stage direction may have led to an entire reevaluation of the play. In performances through the 18th century the ghost generally wore armor throughout, but in Q1 when he appears in Gertrude’s chamber in Act III, he does so “in his nightgown.” “Hamlet is a play about international affairs, about war, about regicide, about many other things,” says Lesser. “But once the focus was placed on this one stage direction, it was easier to imagine that the play was really this family drama around Gertrude’s sexuality. Which is what Freud takes up and then develops more fully into his Oedipal theory of the plot.”

One theory is that Q1 was a pirated script put together by actors who had played bit roles, leaving parts of the text more accurate than others. Hamlet may also be based on an earlier play, now lost, which would help explain the difference in Gertrude’s character and the increased piousness.

After 400 years, Lesser is not sure the mystery will ever be solved, and he’s just as interested in Q1’s own history as a time traveler from the past—a ghost itself. “Scholars had been trying to figure out the origins of the text: Is it Shakespeare’s? Is it a rough draft? Where does it fit?” he says. “But no one had really thought about what happens when a text like this suddenly reemerges after centuries. How do we grapple with the problems it poses?”

Historians and literary critics often dream they’ll come across something no one has seen before, and that it will reveal answers to the questions we have. “But here is a case where it really did happen, and what it did was pose more questions,” says Lesser. “It is a paradox that is always there for us when we think about what we can learn from new discoveries.”