Penn Arts & Sciences Magazine: Scary Outbreaks Distort Our Priorities

Ebola is inescapable. A recent Google News search turned up the following numbers of hits:

Malaria: 98,900

Heart disease: 126,000

AIDS: 524,000

Ebola: 28.1 million

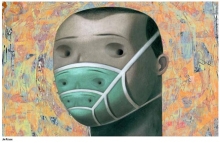

We shouldn’t be surprised: Ebola presses all of the buttons. It is unfamiliar. It comes from an exotic place; outbreaks until this most recent one have been seen only in the Congo River basin—the original “heart of darkness” in Joseph Conrad’s novel. Its symptoms are fascinatingly lurid. It is incurable and often fatal. It is, in short, irresistible. Attention will fade when the epidemic is brought under control in West Africa—or, more likely, even sooner, when isolated cases stop appearing in wealthy countries. But it won’t be long before another scary disease takes its place.

Duke professor Priscilla Wald’s conception of the “outbreak narrative” can help us make sense of our reactions to infectious diseases. An archetypal story of global interdependence, hidden dangers, and scientific expertise, the outbreak narrative has become the primary lens through which we perceive disease threats. It goes like this: Globalization has shrunk the world, rendering all of us vulnerable to hidden dangers lurking everywhere. Those unlike us, often stigmatized by race or class, endanger us as disease carriers. Germs, portrayed as beings with a conscious purpose, invade our country and our bodies like alien armies. Disease detectives persevere through daunting obstacles, aided by cutting-edge technology, and eventually save the day. The heroes of the story are usually doctors or scientists, and its scapegoated villains are most often victims of disease themselves, who through simple carelessness or exotic cultural practices contribute to an outbreak’s spread.

The outbreak narrative reassures us that our science can overcome the threat of strange places and strange people, but it fails as a guide for public health policy in several ways. First, it skews our national health priorities toward the sensational potential pandemic of the moment. In the past twenty years, the examples are legion: Ebola (the first scare), mad cow disease, West Nile virus, SARS, bird flu, swine flu, Ebola (again)—and there are more. Systematically exaggerated threats monopolize public attention at the expense of the everyday conditions that are actually killing Americans (usually slowly) and crippling our economy by driving up health care costs.

Second, the outbreak narrative distracts us from the mundane reality of ground-level health infrastructure: the people and facilities that are the first point of contact for patients and their families in vulnerable communities. This is the most obvious and tragic lesson of Ebola: Individual cases can occur anywhere, but epidemics are impossible wherever health centers or hospitals are capable of diagnosing and isolating cases quickly, and where their staffs have proper training and equipment. Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia are among many developing countries whose health systems suffer from severe funding, staffing, and equipment shortages. These shortages often spell the difference between life and death, and they can be traced at least in part to the structural adjustment policies by which Western lenders have starved the public sector in these countries and forced the privatization of essential services. In such poor regions, rural health centers are not a profitable investment.

We can break out of the outbreak narrative. It is compelling and tenacious, but its stereotypes and distortions need not drive our policies or our discourse. What is required is a forceful and sustained articulation of a new public health vision—one that sees beyond individual disease threats to the deeper structural privations and inequalities that make certain communities more vulnerable to all illnesses.

In this vein, there are lessons to be learned from the Dark Ages before the germ theory of disease revolutionized our understanding of health and illness. Half a century before the bacteriological breakthroughs of Louis Pasteur, Robert Koch, and others, public health was born as a modern field of scientific inquiry and public policy. One of its pioneers was Louis-René Villermé, a French physician and social scientist who co-founded the world’s first public health journal in 1829. In a landmark study of Paris neighborhoods, Villermé was the first to show quantitatively the direct correlation of poverty and mortality. He is also known for his massive two-volume investigation of the occupational and environmental causes of poor health among workers in France’s textile-producing regions.

What is most significant about Villermé’s work is his method. He insisted on rigorous qualitative and quantitative observation of health phenomena “in the field,” where ordinary people lived and worked. He was guided by a few simple questions: Who is sick, and who is healthy? Where, when, and under what conditions? Surprisingly, there is one question that he rarely asked: Which diseases do they have? By looking past specific disease categories, he was able to see the underlying problems that made certain people in certain places susceptible not just to one disease, but to a wide range of health problems.

Villermé’s macroscopic perspective has been eclipsed by the microscopic view that focuses on specific diseases, specific germs, and even specific strands of genetic material in search of weapons with which to fight one disease at a time. This kind of focus allowed us to eradicate smallpox—an astonishing achievement—but it has not necessarily made populations healthier. Malnourished, ill-housed, and overworked bodies that are protected from one germ remain vulnerable to all of the others. Historically, improvements in overall standards of living have done far more than medical interventions have to improve population health.

Imagine a public health system in which threats are evaluated based on their actual magnitude, and by the extent to which feasible interventions would improve overall population health. Imagine a different narrative, in which illness comes from our own environments and our own inequalities, and in which salvation comes not from a laboratory or from hazmat suits but from communities mobilizing to make change happen. It might not be good click bait, but it just might improve our vision.

David Barnes is an assistant professor of history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania.