Penn Researchers Show Bitter Taste Sensitivity Was an Evolutionary Advantage

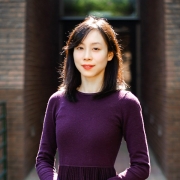

Sarah Tishkoff, Penn Integrates Knowledge Professor in the Department of Biology and Penn Medicine’s Department of Genetics, is senior author of a new study that provides evidence of the significance of bitter taste perception. The study suggests that a genetic mutation making certain people sensitive to bitter compounds appears to have been advantageous, in terms of immune response and metabolism, for certain human populations in Africa.

The study, published in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution, represents the first time that this bitter-taste sensing gene, TAS2R16, was studied in a large set of ethnically and culturally diverse African populations. The gene codes for a molecular receptor that binds salicin, a chemical found naturally in willow bark, the source of aspirin. It acts as an anti-inflammatory but can be toxic in large doses. It is also found in many nuts, fruits, and vegetables.

Researchers asked test subjects to perform taste tests of progressively more concentrated solutions of salicin and report when they could detect a bitter taste. The team also performed a cellular analysis to see the molecular effects of different TAS2R16 mutations. When the researchers mapped individuals’ genetic profiles onto their tasting ability, they found a strong correlation between one of the 15 variants and an increased sensitivity to salicin. The cell-based analysis offered an explanation for this sensitivity: Cells with this genetic mutation had nearly twice as many receptors for salicin as did cells with other forms of the TAS2R16 gene.

On a population level, the researchers found that the high-sensitivity variant for salicin was more prevalent in individuals from East Africa than in those from West Central or Central Africa, and non-Africans possessed only the high-sensitivity version of the gene. What’s more, in East Africans this high-sensitivity variant, which arose roughly 1.1 million years ago, showed signs of being under a force of natural selection in humans, suggesting it conferred a significant evolutionary advantage at some point during our past.

Additional members of the team from Penn included lead author Michael Campbell, as well as Alessia Ranciaro, Daniel Zinshteyn, Renata Rawlings-Goss, Jibril Hirbo, Simon Thompson, and Dawit Woldemeskel. Other collaborators included Alain Froment, Joseph B. Rucker, Sabah Omar, Jean-Marie Bodo, Thomas Nyambo, Gurja Belay, and Dennis Drayna.

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health.

Read the full story here.