Puzzle Pieces

Penn Arts and Sciences Magazine: Spring/Summer 2012 issue

by Blake Cole

Imagine you are watching a slide show and a photo of a beach flashes on the screen. You recognize the scene immediately—you don't have to search for details. The next slide appears: a crowded city street. Though your heart may remain with the beach, your brain has moved on, registering this new location without the slightest hesitation. This ability, called scene recognition, has been the basis of Russell Epstein's research for more than a decade.

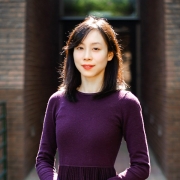

"I was intrigued by how we're able to understand and recognize complex visual scenes," says Epstein, Associate Professor of Psychology. "We have known for quite some time that the brain can figure out what one is looking at very quickly—within a few hundred milliseconds—but we didn't really know much about how it was done or what areas of the brain support this ability."

To better understand the inner workings of scene recognition, Epstein has been using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to measure blood oxygen levels within the brain, highlighting the areas that become active when subjects are shown images. In one recent study, performed in collaboration with Sean MacEvoy, a former Penn postdoc who is now a faculty member at Boston College, subjects were shown specific scenes: a kitchen, a bathroom, an intersection and a playground. They were also shown single objects that might appear in those same environments, like a stove or a bathtub. The pictures are only on the screen for one second—sometimes less.

"The goal is simple. Participants must either name the object or report whether it belongs indoors or outdoors," says Epstein. "This is just to make sure that people are paying attention. What we're really interested in is the perceptual processing of the scene. We monitor the neural signature using fMRI."

In this study, Epstein found that an area of the lateral occipital cortex (LO) is involved in scene recognition—if the recognition is based on correlated objects. These results were a refinement of work that Epstein carried out during a postdoctoral fellowship, where he discovered that a different region of the brain called the parahippocampal place area (PPA) responded very strongly whenever a scene was being analyzed. Whereas the PPA may recognize scenes based on their overall appearance, the LO likely uses objects within the scene to recognize the whole.

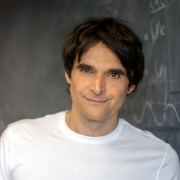

Now, Epstein is pursuing further studies looking at the brain's navigational abilities, working with Lindsay Morgan, a graduate student studying neuroscience. Epstein and Morgan have hypothesized that if a mapping function in the brain does exist, it would be capable of differentiating proximity between two objects and that the brain's activity would reflect real-world distances. In order to test this, they used fMRI to measure the brain activity of undergraduate participants while they were shown pictures of prominent University landmarks like College Hall and Franklin Field. When students were shown two campus landmarks far apart from one another, activity spiked in the hippocampus—even though subjects were never explicitly asked about their locations.

"Previous experiments had shown that the hippocampus is involved in navigation, but we were the first to show that it acts like a map because its activity level tells you how far apart different places are," says Morgan. "This shows that the mapping function of your brain operates automatically whenever you see a familiar place, like a GPS that's always running in the background."

Epstein and Morgan are now investigating the possibility that other brain structures might encode the direction in which participants are facing. This will likely involve showing students pictures of the same landmarks, but from varying sides of an intersection. "In order to navigate around the world, you have to know your bearings," says Epstein. "The brain has to have its own compass."